The end of summer, cook-outs, and retail sales – that’s what Labor Day means in 2011. Although most Americans make a point of enjoying this September holiday, very few of them know it began over a century ago with a violent fight for the rights of laborers, railroad cars, and a President’s campaign for re-election.

The end of summer, cook-outs, and retail sales – that’s what Labor Day means in 2011. Although most Americans make a point of enjoying this September holiday, very few of them know it began over a century ago with a violent fight for the rights of laborers, railroad cars, and a President’s campaign for re-election.

The first Labor Day was celebrated in 1882 in New York City as a workingman’s holiday and a way to smooth over relations between industry and the laboring class who were at that time unionizing to fight for decent wages and working conditions. The idea caught on and spread to other cities, even becoming a state holiday in several states across the U.S. However, it didn’t become a national holiday until 1894, following the Pullman Strike.

George Pullman was the inventor of the Pullman car (a luxury sleeper car) and the vestibuled train (where cars were joined together so passengers could pass from one to the other without stepping outside). Pullman built a company town outside Chicago, where he “shielded” his workers from labor unrest by insulating them from the outside world. Independent newspapers, public speeches, and town meetings were prohibited; homes were routinely inspected for cleanliness. Every aspect of the workers’ lives was directed by the company. An editorial in Harpers Weekly remarked that the power of Otto Von Bismarck, unifier of Germany, was “utterly insignificant when compared to the ruling authority of the Pullman Palace Car Company.”

When an economic depression in 1894 led to decreased revenues, Pullman slashed his workers’ wages, but continued to dock the same amount for rent from their paychecks. Prices in his company run stores remained the same. The workers elected a delegation to protest, but Pullman refused to speak to them. With no other recourse, employees organized a strike, and when the American Railway Union threw their support behind the strikers, their actions crippled railroad transportation across the entire country.

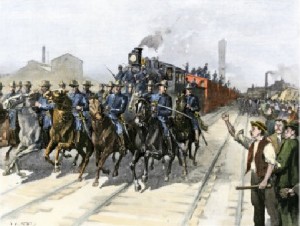

President Cleveland declared the strike illegal under the grounds that it interfered with delivery of U.S. Mail and sent 12,000 U.S. Army troops to break it up. The resulting violence (13 deaths and over 50 wounded) caused a wave of disapproval for Cleveland, who was accused by Illinois Governor Altgeld of putting the U.S. government to work for wealthy industrialists.

Since Cleveland was seeking re-election, he scrambled to redeem his reputation among the laboring class by moving legislation for a National Labor Day Holiday through Congress that same year. Nevertheless, Cleveland was not re-elected.

As for Pullman, he remained so unpopular that when he died in 1897, he was buried in a lead-lined coffin inside a vault reinforced with concrete and steel to prevent desecration of his body.

I don’t like to get too political or preachy on this blog, but suffice it to say I think every American should know more history – but most show too little interest in the subject. Enjoy your Labor Day, everybody, but KNOW why we have one.

holy cow! Soudns like something straight out of a movie! Thankful for the breaks we have today- America was build on the backs of a lot of people:(

Thanks for the timely reminder that’s it’s not all about shopping and grilling. 🙂

I’m old but I think I knew this once. Thanks for the reminder. And Happy Labor Day!

Great historical info! I loved it. 🙂

Good reminder, Dianne, and I didn’t know that about Pullman…hmm, I may be able to use it…thanks 🙂

As a teen I never thought much about holidays or meanings in history but now more than ever I find myself intrigued by each passing holiday. I suppose one day I’ll want to teach my kid what it’s all about… now I’ll know!

Terrific post. (I like the way you think!)

Thank you for sharing this. I didn’t know the history and I’m glad I do now! Great post.

A good, timely post. We’re very close to that original situation today. I don’t understand why we seem seem so passive about it. Have we been dumbed down?

Great history lesson. Wonder why Canada adopted the holiday. Not that I’m complaining. 😀